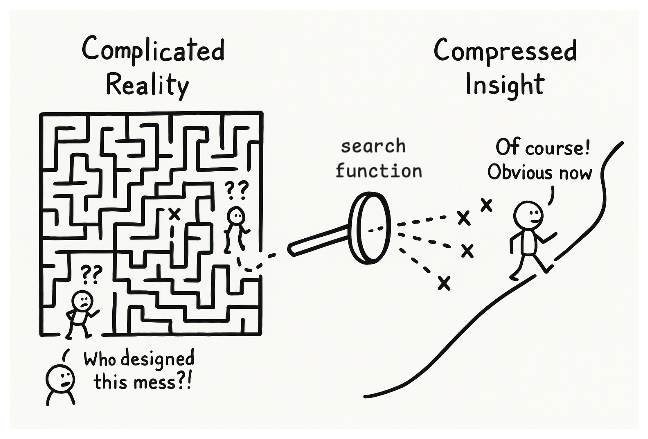

Have you ever felt that rush when a concept suddenly makes sense? That moment when the fog clears and you think, "Of course! Why didn't I see that before?"

That's information compression happening in real time. And there is a reason we need to compress: your brain is tiny (mine too!). Not in size, but in capacity. George Miller's "magical number seven, plus or minus two" isn't academic trivia—it's the hard limit on your working memory. Seven chunks. That's it. That's all you get to play with at once.

Yet here you are, navigating staggering complexity. How? By hunting for better metaphors—more efficient ways to compress reality into something that fits in your head. I want to explore the nature of information compression in metaphors and what metaphors mean to us in this essay.

The Beautiful Compression Machine

"All intelligence is search over Turing machines"

— Gwern Branwen, Dwarkesh Patel Podcast

What does this mean in plain language? Everything complicated is made of simpler pieces correctly arranged. Intelligence is the process of finding those pieces and arrangements—searching through possible patterns until you find ones that compress your observations.

That's a shockingly elegant way to understand intelligence. It's not some magical essence or special fluid: it's a search function.

Think about what happens when you finally "get" a difficult concept. You're not creating new knowledge; you're discovering a shorter path through territory that already exists; you're compressing.

This explains why the greatest insights often feel obvious in retrospect. They are obvious—once you have the right compression algorithm.

The Hitchhiker's Problem

But it doesn't help if you learn a better compression but don't know the steps to get to it. Let me tell you about the most elegant joke ever told about compression. In "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," a supercomputer named Deep Thought spends 7.5 million years calculating the Answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything. The answer, famously, is "42."

The joke isn't that the answer is meaningless. The joke is that compression without scaffolding is meaningless. The characters receive pure output, "42", without any of the intermediate steps, reasoning, or even the Question it answers. It's theoretically the endpoint of perfect compression. But it's useless because they lack the cognitive scaffold; the millions of years of metaphorical steps and conceptual development aren’t given that would make "42" interpretable.

The Joy of Getting It

The journey is just as important as the destination, and we are biologically wired to seek this pleasure even if the journey is difficult—we are in the words of Jürgen Schmidhuber, a pioneer of modern AI, "Driven by Compression Progress." The brain, he argues, generates curiosity reward whenever it improves its ability to compress observations.

"Curiosity is the desire to create or discover more non-random, non-arbitrary, regular data that is novel and surprising... because its regularity was not yet known."

This explains why neither random noise nor blank walls interest us for long. White noise (high Shannon entropy (think: completely random information)) contains no compressible patterns. A blank wall (low entropy, (think: no novel information)) is already maximally compressed. The sweet spot is data with undiscovered regularities—patterns you're just about to crack.

Side-note: Schmidhuber argues that subjective beauty equals compressibility relative to the observer's knowledge. But what's interesting isn't what's already compressed—it's what's becoming more compressible through learning. He defines "interestingness" as the first derivative of subjective beauty: the steepness of your personal learning curve.

When a joke makes you laugh, a puzzle solution clicks, or a song's unexpected chord change delights you, you're experiencing compression progress. Your brain just found a shortcut through complexity. That's not incidental pleasure, it's the entire point of the system.

Compression Failures: When Metaphors Break

Not all compression attempts succeed. Sometimes we try to force new knowledge into old metaphors, and the result is confusion, not clarity. Science is a constant advance through confusion.

Remember when we first learned about atoms? Most of us got the "solar system" metaphor: electrons orbiting a nucleus like planets around the sun. Tidy. Intuitive. Wrong.

Quantum mechanics destroyed this compression. Electrons aren't little planets. They're... something else. Wave-particle duality, probability clouds, quantum tunnelling—these feel awkward, don't they? These concepts resist our familiar spatial metaphors and I require a different context to understand them.

Physicist Richard Feynman famously said, "If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don't understand quantum mechanics." And who knows, maybe this isn’t the final frontier of understanding?

The history of science is full of these failures. Phlogiston. Luminiferous aether. The four humours. Each represents a metaphorical compression that initially seemed promising but ultimately collapsed under contradictory observations.

This is why true learning often feels uncomfortable. It's not just adding new information, it is also restructuring your compression algorithms, often painfully.

In other words, when our old metaphors break, we're forced to seek better ones—painfully restructuring how we compress reality.

Building the Ladder: Why You Can't Skip Steps

Learning is inherently constructive. We don't simply absorb information; we integrate it into existing mental structures that we've been building since childhood.

Think of it as a ladder. Each rung must rest on the one below. Metaphors are the rungs. Trying to jump too many leads to confusion or shallow understanding.

This is why you can't just tell someone the answer. This is why "just watch YouTube" isn't how people master calculus. This is why Deep Thought's "42" was useless without the question.

Knowledge must be built, rung by rung. Each metaphor rests on the ones below it.

Each successful step up this ladder provides the "compression progress" reward that Schmidhuber describes. Learning feels good when it's working. When you're making progress.

This explains why education fails when it tries to skip the scaffolding process. The brain physically cannot integrate new knowledge without connecting it to something it already knows. There are no shortcuts.

Recognising this scaffolding imperative suggests a clear strategy for education: prioritise building durable, reusable metaphors rather than isolated facts. The best teachers don't just deliver information—they craft metaphors that serve as cognitive handholds on otherwise slippery concepts.

The Searchers: Artists and Scientists

"It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child."

— Pablo Picasso

Scientists and artists seem like opposites. One seeks objective truth; the other, subjective expression. But in Schmidhuber's framework, they're fundamentally alike. Both search for simple but new laws or connections that compress observations.

Scientists invent experiments to discover previously unknown laws that compress observed data. Artists combine familiar elements in novel ways to reveal previously unnoticed regularities.

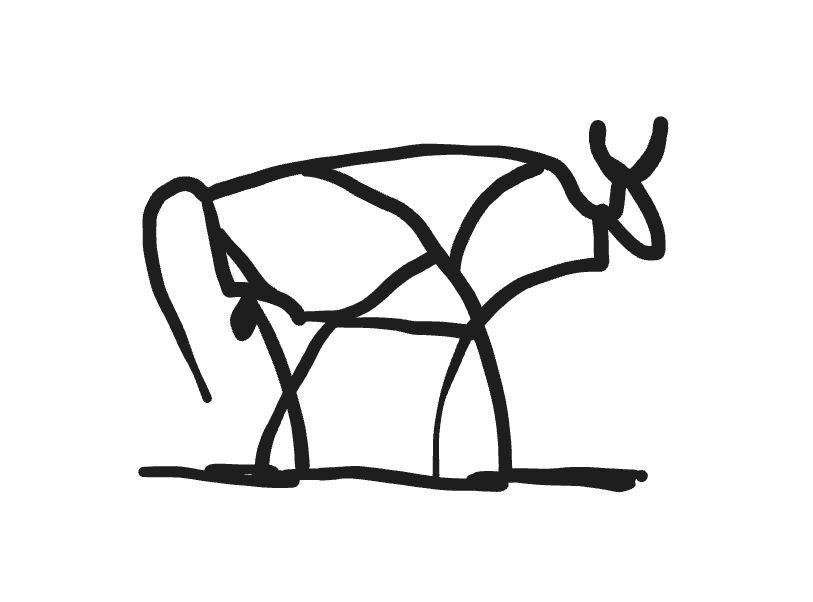

Consider E = mc². Three symbols that compress volumes of physical observations. Or Picasso's bull—a few essential lines that capture the essence of "bullness" more powerfully than photographic detail. Both Picasso's bull and Einstein's equation compress rich complexity into powerful metaphors—patterns we can readily grasp and apply.

Yours truly’s attempt at Picasso’s Bull.

Yours truly’s attempt at Picasso’s Bull.

The distinction between creators and observers blurs too. When you focus attention on artwork that exhibits previously unknown regularities, you're getting the same fundamental reward as the artist who created it. Both execute sequences that expose new compressibility.

This explains the uncanny similarity between scientific and artistic revolutions. Both involved throwing out old compression algorithms—perspective in Renaissance painting, Newtonian mechanics in physics—and replacing them with new ones that revealed previously invisible patterns.

Humans vs. Machines: The Compression Gap

According to Gwern, humans excel at abstraction—identifying and manipulating "atoms of meaning" through abstraction. Machines struggle to create truly reusable and generalisable patterns.

This presents both challenge and opportunity in the age of AI.

AI excels at synthesis—recombining known elements into coherent outputs. But it struggles with true abstraction—extracting reusable patterns from minimal examples. Ask GPT-4 to count the letter 'r' in "strawberry," and it might fail—a trivial task for humans.

Why? Because the AI lacks genuine symbolic reasoning. It can't step outside its statistical patterns to apply abstract rules. It can't truly compress.

Meanwhile, humans struggle with exactly what AI excels at: processing vast amounts of data without forgetting. Our seven-chunk working memory is pathetically small compared to the billions of parameters in modern AI systems.

But our compression abilities remain unmatched. We can take a few examples and extract a general principle. We can see one instance of a pattern and recognise it everywhere. We can reason about abstractions of abstractions of abstractions.

Our uniquely human advantage remains clear: we're exceptionally good at creating flexible metaphors, allowing us to compress and abstract in ways machines currently cannot.

This is why, in a world increasingly dominated by AI, the most valuable human skill may be precisely this: the ability to find better metaphors—to compress reality in ways machines cannot.

The Hunt Continues

So where does this leave us? We're pattern-matchers and complexity-reducers by necessity. We hunt for better metaphors because we must. This is how we make an incomprehensibly complex world fit into our seven-chunk working memory.

The pleasure isn't in the endpoint; it's in the steepness of the curve. Not in knowing, but in learning.

This explains so much about human behaviour. Why puzzles delight us but spoilers ruin them. Why jokes aren't funny when explained. Why the "aha!" moment can't be given but must be earned.

Understanding isn't a destination but an ongoing activity where we are building, testing, and improving our metaphorical models of the world.

Perhaps the search for meaning itself is just a search for an "ultimate metaphor"; but, given our cognitive limits and the complexity we face, maybe the most meaningful stance is to embrace the process: the endless, rewarding journey of hunting for better metaphors.

Yet, while metaphors are vital, relying solely on them risks oversimplification. True understanding sometimes requires stepping beyond metaphor to grapple directly with complexity. The best thinkers know when to use an existing metaphor as a tool and when to set them aside and seek a new one.

After all, the joy isn't in having compressed. It's in compressing.