In Part 2, we will continue analysing large language models' ability to handle the Irish language using over 1100 grammar questions. You can check out Part 1 or read the recap below, before we dive into the performance of Reasoning Models.

Recap from Part 1: Non-reasoning models perform well

Anthropic's Claude 3.5 and OpenAI's GPT-4.1 scored top with 73.08% and 71.81% respectively. Their scores showed how even traditional models can excel at grammar tasks thanks to better representations of hierarchical linguistic rules, but there is still so much room for growth: all models struggled on more complex features and suggest that they may be relying more on memorised patterns without fully capturing the underlying grammar.

Now that we're caught up, let's look at what a reasoning model is.

What is a Reasoning Model?

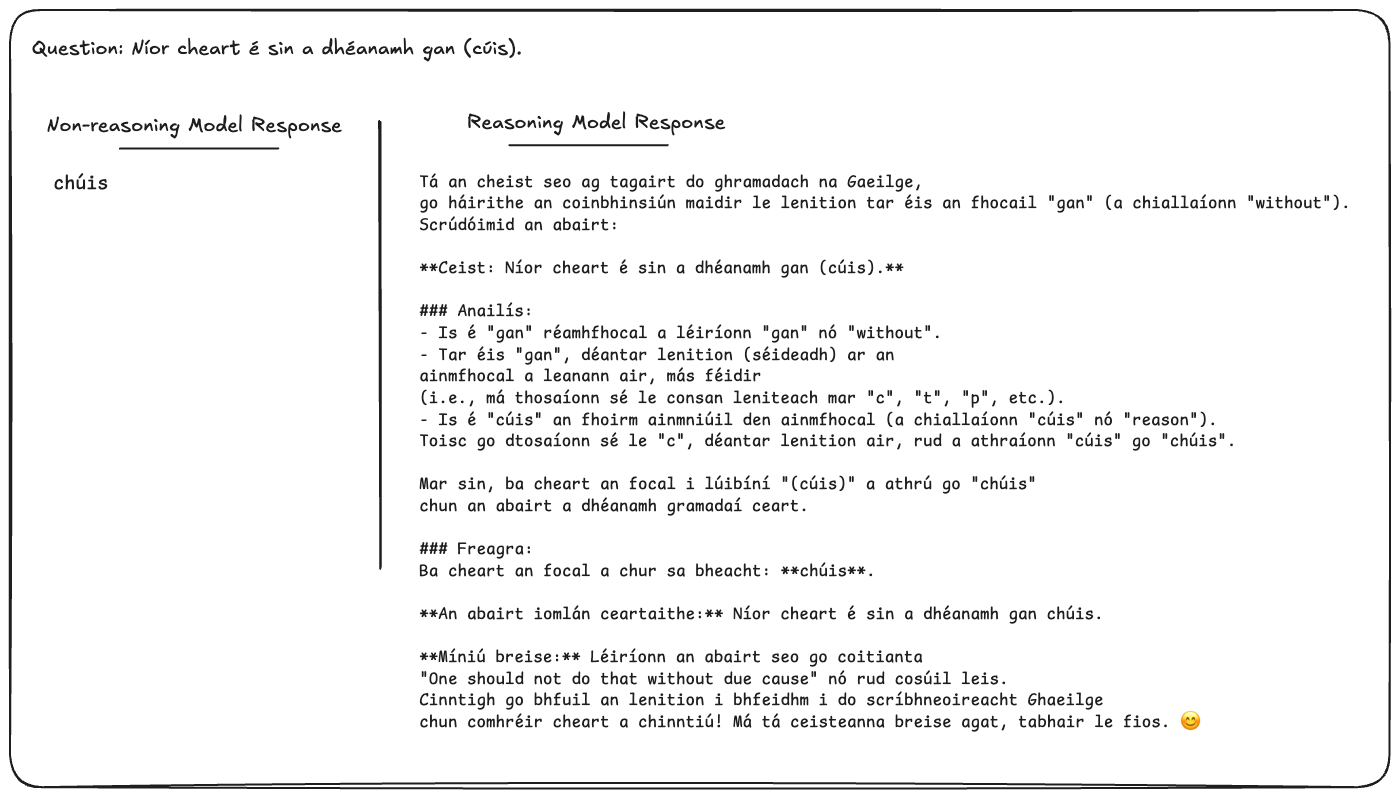

Example query with response from a non-reasoning LLM (GPT-4o) and a reasoning model (Grok-3-Beta). I am willing to forgive some of the ungrammatical and plain incorrect Irish that is in the reasoning model's response so long as it gives the correct answer.

Reasoning models are still relatively new to the scene, so I just want to break down what they do first. When considering how language models process information, we can draw a distinction between models that primarily rely on predicting the next token based on learned patterns and those enhanced with reasoning capabilities. A typical large language model excels at identifying and reproducing patterns from its training data to predict the most probable next word or token in a sequence. As Sebastian Raschka describes in Understanding Reasoning LLMs, these models often generate responses for tasks not requiring reasoning based on pattern matching and without explicit intermediate steps.

Reasoning models, however, are designed to go beyond this probabilistic token prediction and simple pattern completion. They are engineered to break down complex problems into intermediate steps, process information sequentially, and build a logical chain to arrive at a solution. This deliberate, step-by-step approach allows them to tackle tasks that require more than just completing learned patterns, enabling them to work through a problem rather than merely predicting the most likely next token. This makes them particularly effective for problems like mathematical proofs, coding challenges, and intricate puzzles, where breaking down the problem and following a logical sequence is crucial. While many standard LLMs can exhibit some basic reasoning, models specifically developed for reasoning, like those discussed by Raschka, are optimised for more complex, multi-step reasoning tasks. However, it's important to note, that reasoning models can sometimes be prone to overthinking and may not always be the most efficient or suitable choice for simpler tasks like basic translation or summarisation.

My baseline hypothesis here is that reasoning models will perform better on more complex grammatical tasks but their accuracy will suffer for simpler grammatical features.

Reasoning Models we are looking at

In this analysis, we examine the performance of several reasoning models, including:

- xAI’s Grok 3 beta and Grok 3 mini beta

- Deepseek’s R1

- OpenAI’s o1, o3 and o3-mini

It's worth noting that at the time of this research, Anthropic had not released a fully reasoning model; their Claude Sonnet is considered a hybrid with some reasoning elements. Deep thinking is another approach to achieving similar capabilities, though it was not utilised in this specific study. Based on the results we will discuss, we can revisit the potential impact of such approaches in the future.

Dataset and Methodology

Like in Part 1, we have over 1100 questions that are spread across 20 features of grammar. We get the model to generate a response based on the prompt without any additional context, and then extract the answer. The answer is first checked by AI to save time and then checked by myself.

Results

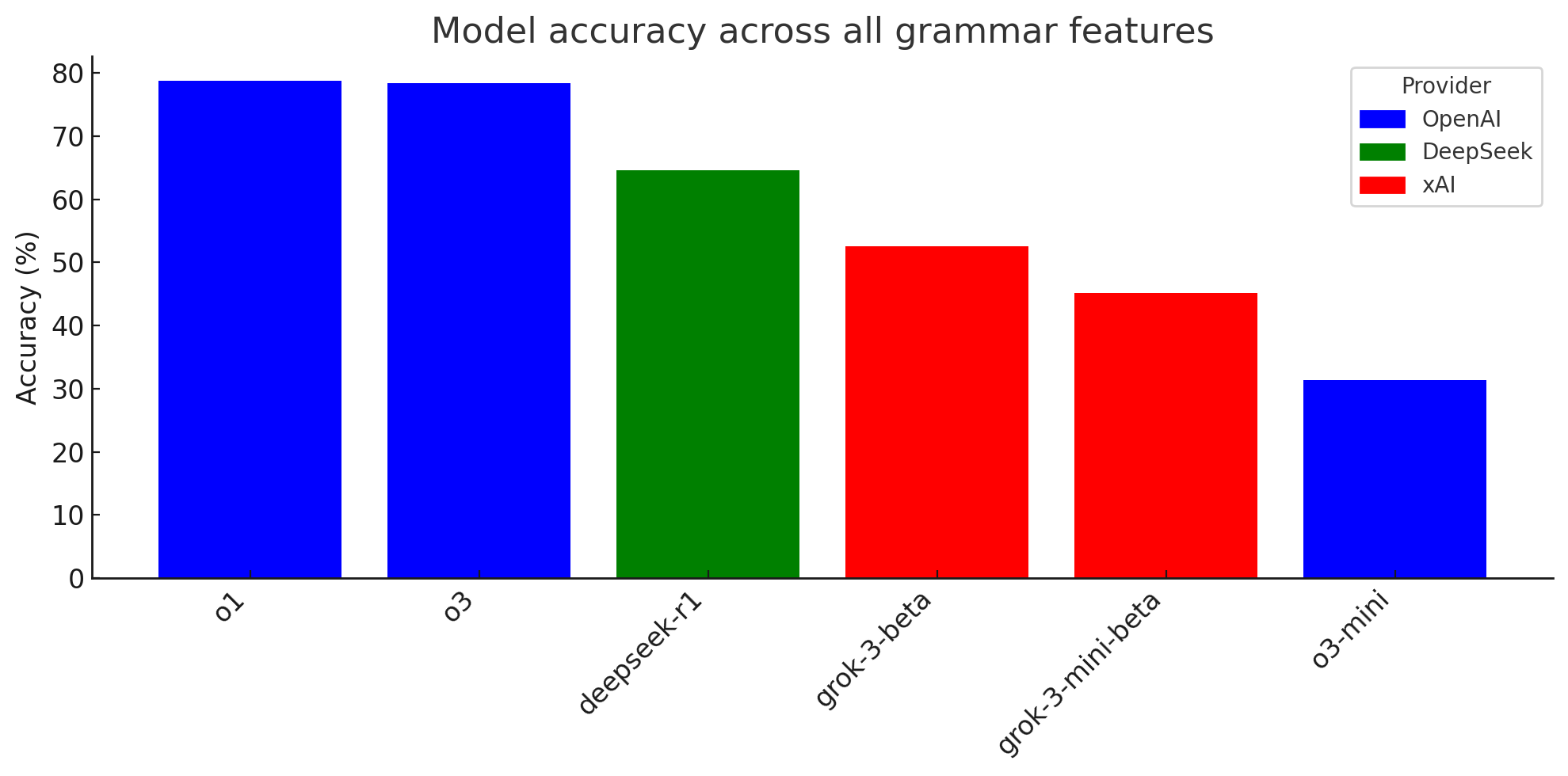

Looking at the performance of the reasoning models across the 20 grammatical features, we see varied accuracy considerably. The overall accuracies for the reasoning models are as follows:

- OpenAI's o1 - Accuracy: 78.79%

- OpenAI's o3 - Accuracy: 78.36%

- DeepSeek's R1 - Accuracy: 64.65%

- X-ai's Grok 3 beta - Accuracy: 52.56%

- X-ai's Grok 3 mini beta - Accuracy: 45.14%

- OpenAI's o3-mini - Accuracy: 31.35%

Overall, OpenAI's o1 and o3 models demonstrate the highest accuracy among the reasoning models, performing significantly better than DeepSeek R1 and the Grok models. o3-mini shows considerably lower accuracy compared to its larger counterparts.

The Good

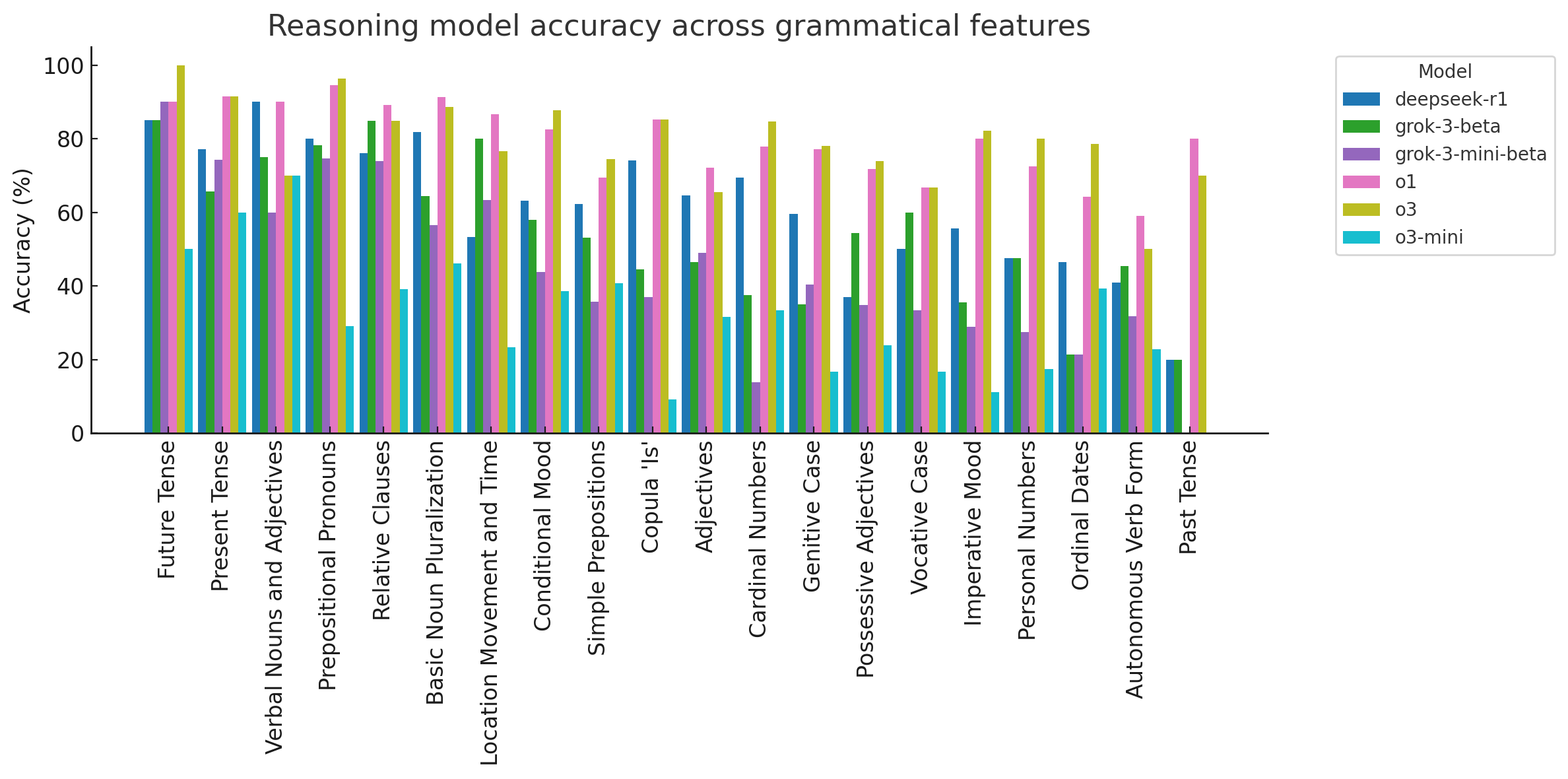

Looking at the feature-by-feature breakdown, the reasoning models demonstrated strong performance in several areas. Notably, OpenAI's o1 and o3 models consistently achieved high accuracies across many features. Some areas where reasoning models, particularly o1 and o3, excelled include:

- Basic Noun Pluralisation: o1 and o3 both achieved over 88% accuracy, showing a strong grasp of fundamental noun forms.

- Present Tense: o1 and o3 again performed very well, both exceeding 91% accuracy, indicating proficiency with regular verb conjugations.

- Prepositional Pronouns: o1 and o3 had accuracies above 94%, demonstrating a solid understanding of these common forms. This is fascinating because this is decidedly multi-step, particularly in phrasal verbs like “afraid of someone: (eagla roimh x); the models' success here implies they can:

- Identify the English prepositional phrase (e.g., “of him”).

- Map it to the correct Irish preposition (e.g., "of" in "afraid of" often maps to roimh).

- Select the correct Irish pronoun (“sé” for “him”).

- Form the correct prepositional pronoun (roimh + sé = roimhe).

- Integrate it into a grammatically correct Irish sentence structure.

- Copula 'Is': A fundamental challenge is knowing when to use “is” versus “tá”. “Is” is generally for defining or equating (X is Y, where Y is a noun or pronoun defining X), while “tá” is for describing states, locations, or actions (X is [adjective], X is [at a place], X is [doing something]). o1 and o3 achieved over 85% accuracy, handling the complexities of the copula effectively.

These results indicate that the leading reasoning models are capable of handling both regular and some more complex grammatical features in Irish.

The Bad

Despite their strengths, the reasoning models, like their non-reasoning counterparts, still struggled with certain aspects of Irish grammar. This is particularly evident in grammatical features that are unique to Irish or have complex, interacting rules, which pose significant challenges regardless of reasoning capabilities. Areas where performance was generally low across most reasoning models include:

- Autonomous Verb Form: This unique feature of Irish grammar continued to be a significant challenge, with even the best reasoning models (o1 and o3) only reaching around 50-59% accuracy. Often the models ignored the form completely and tried to formulate sentences that still used regular ‘it’ pronouns.

- Past Tense: While o1 and o3 showed improvement in this area compared to some non-reasoning models (reaching 70-80%), DeepSeek R1 and the Grok models still performed poorly (around 20%). The better performance of o1 and o3 suggests their reasoning capabilities allow them to better handle the multi-step nature of past tense formation (particle + stem + mutation). However, the continued struggles of other reasoning models indicate that reasoning alone isn't a panacea if the foundational knowledge of irregular forms and specific mutation rules isn't robustly learned, likely due to insufficient or unclear patterns in their training data for these specific, often idiosyncratic, grammatical features.

- Ordinal Dates: Accuracies for this feature were generally in the 40-78% range across reasoning models, indicating inconsistency in handling these specialised forms. Irish ordinal numbers—e.g., an chéad (1st), an dara (2nd), an tríú (3rd), an t-aonú lá déag (11th), an dara lá is fiche (22th)—have unique and sometimes irregular formations, especially for numbers beyond ten. They often involve multiple words. Models might not have enough exposure to the full spectrum of these multi-word ordinal constructions to generalise the patterns correctly. They might default to cardinal numbers or simpler, incorrect ordinal forms.

- Personal Numbers: Similar to ordinal dates, personal numbers (used for counting people) presented difficulties, with accuracies ranging from 17.5% to 80%. This suggests that specific, less frequent grammatical constructs are harder to learn.

These persistent areas of weakness suggest that while reasoning helps with multi-step transformations, it doesn't fully compensate for a lack of sufficient training data on less common or highly irregular grammatical features. The models may still be relying on patterns that are less reliable in these complex cases.

The Differences

Examining the performance across the reasoning models themselves reveals some notable differences in certain grammatical features. These discrepancies can offer insights into the varying strengths and weaknesses of these models:

- Past Tense: While o1 and o3 performed relatively well (70-80%), DeepSeek R1 and the Grok models had significantly lower accuracies (around 20%). This large gap suggests that o1 and o3's reasoning capabilities might be more effective at handling the irregular patterns and mutations required for the past tense compared to the other reasoning models. The lower-performing models appear to oversimplify, misapply rules, or lack the fine-grained knowledge of exceptions and specific constructions, particularly when faced with irregularities or complex syntactic structures like negation, nach.

- Ordinal Dates: o3 achieved a high accuracy of 78.57%, while other reasoning models ranged from 21.42% to 64.28%. o3's superior performance on ordinal dates stems from its more robust handling of the multiple, interacting grammatical rules involved: forming the ordinal number itself, correctly using "lá" and "mhí", applying the correct genitive (and article) for the month name, and managing initial mutations. The other models showed inconsistencies in one or more of these areas.

- Personal Numbers: o3 again led with 80% accuracy, while other reasoning models varied widely (17.5% to 72.5%). o3 is generally better at making this distinction and applying the subsequent rules (genitive plural after personal numbers, nominative singular after cardinal numbers 1-10 for non-humans). For example, in a translation for “three men", o3 correctly uses “triúr fear”. For “three dogs”, it correctly uses “trí mhadra”. Lower-performing models sometimes confused these or misapplied the rules. For example, o3-mini “triúr fir” (using nominative plural *fir* instead of genitive plural *fear*). For “three dogs”, it gave "trí madraí" (using nominative plural, madraí, instead of nominative singular, madra, after trí). DeepSeek R1 and Grok models also showed similar errors in these questions, indicating a less secure grasp of when to use personal vs. cardinal numbers and the distinct grammatical patterns they trigger.

- Vocative Case: Accuracies ranged from 16.66% (o3-mini) to 66.66% (o1 and o3), showing a considerable spread. This might be due to differing abilities in applying the required initial mutations and vowel changes. If the training data for less common names or specific surname structures in the vocative is sparse, models will struggle to generalise the rules correctly and may produce forms that are orthographically incorrect or miss subtle but necessary changes. The accuracy suggests that models have some grasp but lack the fine-grained knowledge for consistent performance. The vocative case is a good example of where reasoning might help in applying a sequence of rules (particle + lenition + slenderisation — final mutation of changing vowels e.g. man → men: fear → fir), but if the underlying knowledge of those rules and their exceptions (especially lexical irregularities) is weak due to data limitations, even reasoning models will falter.

- Genitive Case: o1 and o3 performed well (around 77-78%), while o3-mini and Grok 3 beta had much lower accuracies (around 16-35%). The genitive in Irish is a multifaceted grammatical feature requiring:

- Accurate Noun Classification: Identifying a noun's gender and declension class, which dictates its genitive pattern.

- Correct Article Transformation & Mutation: Modifying the definite article (e.g., 'an' to 'na') and applying the correct initial mutation (lenition, eclipsis, h-prefixing) to the noun.

- Appropriate Noun Ending Modification: Altering the noun's ending according to its declension, which can involve slenderisation/broadening of consonants, vowel changes, or specific suffixes.

- Handling of Irregularities: Recognising and correctly forming the genitive for numerous irregular nouns (e.g., “clárseach” becoming “cláirsí”).

- Correctly Identifying the Target for Genitisation: In possessive phrases like X of Y (“X an Y”), understanding that Y takes the genitive form while X often remains nominative (e.g., “blas an fhíona” – “taste of the wine”).

o3-mini and Grok 3 beta struggled with the level of nuance. Depending on the commonality of the word or phrases, their errors may stem from misclassifying nouns, inconsistently applying mutation or article rules, overgeneralising common ending changes (thus failing on irregulars), or incorrectly identifying which noun in a phrase needs to be in the genitive. This suggests their internal grammatical models are less nuanced, leading to a heavier reliance on surface pattern matching which is insufficient for the genitive's systemic complexity.

These differences among reasoning models could be attributed to variations in their training data, model architecture, or the specific techniques used to enhance their reasoning abilities. Models that are better at breaking down complex transformations into sequential steps, likely perform better on features like the Past Tense and Copula.

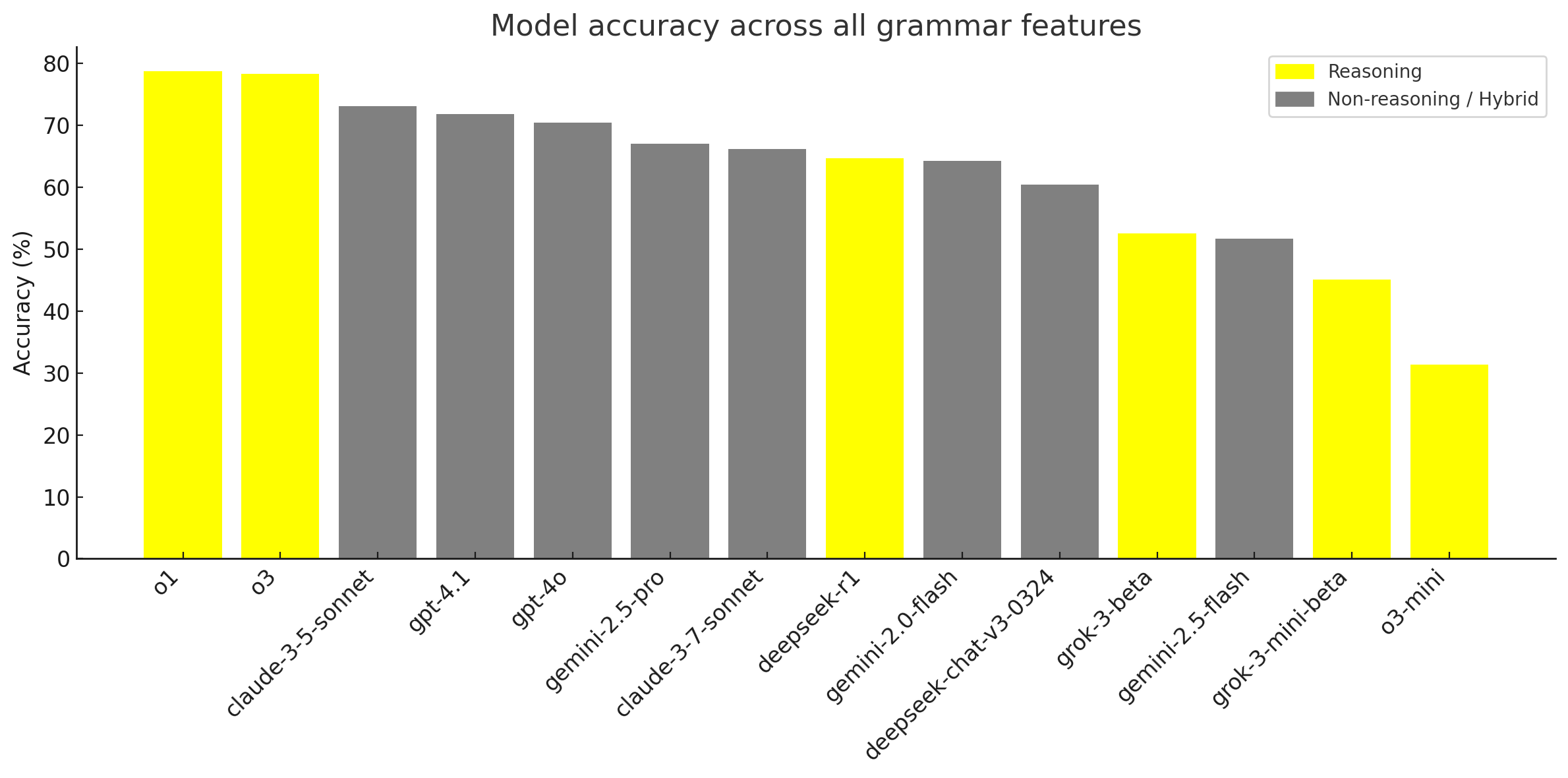

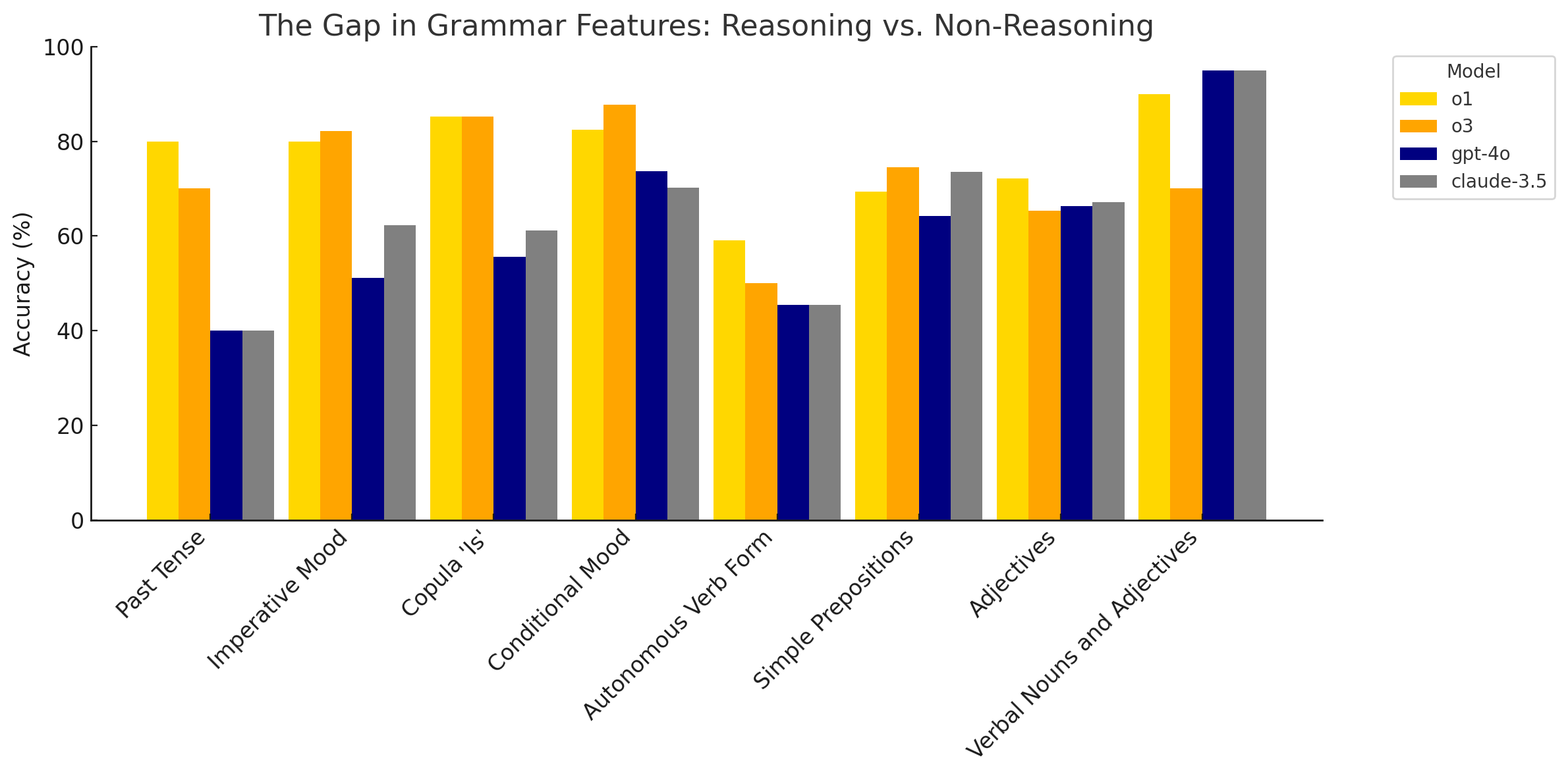

Comparison of Leading Reasoning Models vs Non-Reasoning Models

To understand the impact of reasoning capabilities, we conducted a deep comparison between the top-performing reasoning models (OpenAI's o1 and o3) and the leading non-reasoning models from Part 1 (Anthropic Claude 3.5 and OpenAI's GPT 4.1). This comparison highlights where reasoning provides a significant advantage and where other factors might be more influential.

The Same

Interestingly, there were several areas where the leading reasoning models (o1 and o3) and the leading non-reasoning models (Claude 3.5 and GPT-4.1) exhibited similar performance, both in terms of success and struggle.

For grammatical features that are largely rule-based and surface-level, requiring rote application of patterns rather than complex, multi-step logic, all four models tended to perform comparably well. Examples include Basic Noun Pluralisation, where accuracy ranged from 84% to 91%, and Present Tense conjugation, with accuracies between 83% and 91%. In these cases, the core noun-form recognition and regular conjugation patterns are straightforward enough that neither chain-of-thought reasoning nor extra context significantly altered performance, resulting in tightly clustered scores.

Conversely, there were also areas where all four models struggled to a similar degree. The Vocative Case, involving lenition, vowel changes, and optional article drop, proved challenging for all, with accuracies ranging from 63% to 67%. The errors here were often orthographic, and neither reasoning nor larger context seemed to compensate effectively. Similarly, Simple Prepositions tripped up every model comparably, leading to middling, tightly-grouped scores between 62% and 75%. This consensus weakness appears to stem from the presence of many small, irregular forms rather than a need for multi-step logic.

The Biggest Differences (Reasoning Better!)

In contrast to the areas of similar performance, there were several grammatical features where the reasoning models, particularly o1 and o3, demonstrated a significant advantage over the non-reasoning models. This divergence highlights the impact of reasoning capabilities on tasks requiring sequential decisions and transformations (see table at end of section).

The most striking difference was observed in the Past Tense, where the reasoning models achieved an average accuracy of 75%, a substantial 35 percentage points higher than the non-reasoning models' average of 40%. Forming the past tense in Irish requires multiple steps, including picking the correct stem, applying lenition, and handling irregular forms. o1 and o3's ability to chain these sub-steps appears to be the key to their success, while non-reasoning models often faltered after the initial lenition, missing the necessary stem change.

Similarly, the Imperative Mood showed a 20 percentage point gap, with reasoning models averaging 81% compared to 61% for non-reasoning models. The imperative demands handling subject-free verb forms and negative particles, another multi-step transformation that reasoning models completed more reliably. The Copula “Is” also revealed a significant advantage for reasoning models (85% vs 63%), as it requires re-ordering elements and ensuring pronoun agreement—tasks that benefit from a structured reasoning process.

Other areas where reasoning models showed a notable lead include the Conditional Mood with “má/da”, with an 18 percentage point gap (85% vs 68%), likely due to the long-range dependencies involved, and the Autonomous Verb Form, also showing an 18 percentage point difference (55% vs 36%).

This pattern suggests that whenever an exercise demands a sequence of decisions or transformations, the reasoning-enabled models gain a considerable advantage. Their ability to break down complex tasks into intermediate steps allows them to navigate the intricacies of Irish grammar more effectively in these specific areas.

The Biggest Differences (Non-Reasoning Better?)

Interestingly, there were also instances where the leading non-reasoning models (Claude 3.5 and GPT-4.1) performed better than the leading reasoning models (o1 and o3). While these gaps were generally smaller than when reasoning models excelled, they are worth noting:

- Simple Prepositions (Combined): Claude 3.5 and GPT-4.1 had accuracies around 73.4%, while o1 and o3 were slightly lower at around 69-74%. This suggests that for some more straightforward, perhaps more frequently encountered patterns like simple prepositions, the extensive training data of the non-reasoning models might give them a slight edge.

- Adjectives (Combined): GPT-4.1 and Claude 3.5 had accuracies around 73.8% and 67.08% respectively, while o1 and o3 were around 72.15% and 65.4%. This difference, though not massive, could again point to the non-reasoning models' strength in pattern recognition on broader linguistic features.

- Verbal Nouns and Adjectives: Claude 3.5 and GPT-4o (from Part 1) excelled here (95%), while o1 and o3 were around 90% and 70%. This might indicate that for certain derivational morphology tasks, the non-reasoning models' training has provided a stronger foundation or that the reasoning models simply overthought.

These cases where non-reasoning models performed better could be due to the nature of the tasks being less reliant on complex, multi-step reasoning and more on recognising and applying learned patterns from the training data. If a pattern is very common and regular, a non-reasoning model might be just as, if not more, effective at applying it quickly without the overhead of a reasoning process.

Learnings, Conclusions & Next Steps

The analysis of reasoning models on the Irish grammar test suite provides several key takeaways, reinforcing the importance of developing AI that can effectively handle lower-resource languages like Irish to support language preservation and bridge the digital language divide. Firstly, leading reasoning models like OpenAI's o1 and o3 demonstrate a clear advantage in handling grammatical features that require multi-step transformations and logical sequencing, such as the Past Tense, Imperative Mood, Copula “Is”, and Conditional Mood. This supports the idea that their enhanced reasoning capabilities enable them to break down and solve more complex linguistic problems more effectively than models relying primarily on pattern matching.

However, reasoning models still struggle with highly irregular forms and grammatical features that are less common in their training data, such as the Autonomous Verb Form and Personal Numbers. This suggests that while reasoning is a powerful tool, it does not entirely compensate for a lack of sufficient exposure to specific linguistic phenomena.

The comparison between reasoning and non-reasoning models also revealed areas where performance was similar, particularly in rule-based and surface-level tasks like Basic Noun Pluralisation and Present Tense. This indicates that for straightforward grammatical applications, the benefits of explicit reasoning might be less pronounced. Non-reasoning models showed a slight edge in some areas like Simple Prepositions and certain Adjective uses, potentially due to their extensive training on broad linguistic patterns.

The differences observed among the reasoning models themselves highlight that the implementation and effectiveness of reasoning capabilities can vary. Models that are better at sequential decision-making appear to perform better on complex transformations.

Overall, the findings suggest that reasoning models represent a significant step forward in handling complex grammatical structures in lower-resource languages like Irish. While there are still areas for improvement, particularly with highly irregular or rare features, the ability of these models to reason through multi-step linguistic processes offers promising avenues for future language technology development and preservation efforts.

Building on the insights gained from evaluating both non-reasoning and reasoning models, the next phase of this research will explore methods to further enhance LLM performance on Irish grammar. The next step will be adding more context now that we have ascertained the baseline. A key area of investigation is the impact of providing models with explicit grammatical rules. For example, we will test whether explaining complex features like the autonomous verb form before prompting the models leads to improved accuracy. Additionally, we plan to experiment with using tools and external data sources to enrich the models' knowledge and understanding of Irish, aiming to close the performance gap on challenging grammatical features. This iterative approach seeks to identify effective strategies for leveraging AI to support and preserve lower-resource languages.