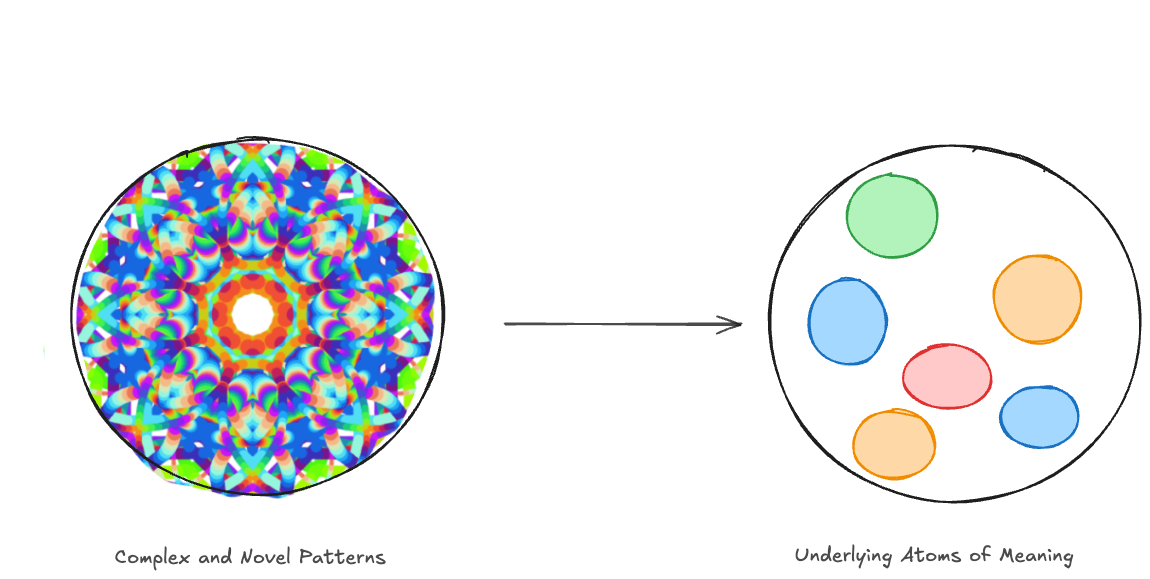

Have you ever looked through a kaleidoscope? Inside its narrow tube, tiny fragments of glass and mirrors reflect light, creating dazzling patterns that seem endlessly unique. Yet, beneath this apparent complexity lies a simple truth: all these intricate designs are constructed from just a few fundamental elements, rearranged and recombined. François Chollet’s kaleidoscope hypothesis applies this principle to the world itself. Beneath the surface complexity of any domain, there exists a finite set of “atoms of meaning,” simple building blocks that can be abstracted and recombined to navigate new challenges.

This kaleidoscope hypothesis was originally posed as a way to understand intelligence but I believe it can be used as a framework for rethinking education in the age of artificial intelligence (AI). AI systems like large language models (LLMs) excel at synthesising known elements, but they falter when faced with tasks that are truly novel; additionally, they are great at breaking concepts down — explain it to me like I am a five year old — but again, when asked to truly abstract to generalisable patterns (see below for addition) it still fails miserably. As AI continues to transform rote and repetitive tasks, humans must focus on what sets us apart: our capacity for abstraction, for identifying and manipulating the fundamental patterns of the world. Education must shift toward teaching these deeper principles, emphasising understanding over memorisation, more so than ever before—and not just because rote learning is boring.

The Kaleidoscope Hypothesis and Intelligence

The kaleidoscope hypothesis suggests that the apparent complexity of the world is rooted in a subtle simplicity. Intelligence, both human and artificial, in the mind of Chollet, involves perceiving the “atoms of meaning” within this complexity, extracting these reusable patterns, and recombining them to solve new problems. This process has two key components: abstraction and synthesis.

Abstraction is the ability to distill raw information into general, reusable patterns. These patterns serve as foundational templates that can be applied across different contexts.

Synthesis involves assembling these building blocks to model or solve a problem in a domain. It is the process of recombination, constructing something new from familiar parts.

Humans excel at both abstraction and synthesis, leveraging their ability to see patterns, extract generalisable principles, and adapt them creatively to new situations. But how do machines compare?

Synthesis in AI: Where Machines Excel

We have seen that synthesis is one of AI’s stronger capabilities, with many people in tech and marketing fearing for their jobs and many jobs indeed being lost to automation. By recombining learned patterns, models like LLMs can generate coherent text, solve structured problems, and create outputs that appear novel. This strength comes from their ability to interpolate—working within the bounds of their training data to combine familiar elements in meaningful ways.

For instance, AI excels at:

- Language Models: LLMs like OpenAI’s GPT-4 can generate coherent essays, complete code snippets, and craft responses by combining learned patterns. For instance, developers use GitHub Copilot, powered by OpenAI’s Codex, to assist in writing code by suggesting entire functions or lines based on the context.

- Structured Problem Solving: AI applies predefined rules to organise data into coherent outputs. For example, Google’s AlphaGo utilised deep neural networks and tree search techniques to master the game of Go, effectively recombining known strategies to outperform human champions.

However, AI’s Capabilities Are Limited:

- Bound by Training Data: AI struggles with tasks requiring creativity or novelty beyond its training data. For example, when asked to generate a story in a completely new genre without prior examples, an AI might fail to produce a coherent narrative, as it lacks the necessary reference points.

- Surface-Level Recombination: AI often produces outputs that combine elements without understanding their deeper relationships. An instance of this is AI-generated art that blends styles from various artists, resulting in images that, while visually appealing, may lack the nuanced intent or emotional depth present in human-created art or present brush-strokes that wouldn’t be possible to be made in reality.

As Chollet has noted, language models are interpolative databases. It can synthesise within familiar boundaries but cannot make “new science” or push into realms requiring deep creativity or originality.

Abstraction in AI: A Fundamental Weakness

Abstraction is where AI faces its greatest challenges. While machines are excellent at recognising patterns in well-defined datasets, their abstractions are often superficial and tied to the constraints of their training.

AI’s strengths in abstraction include:

- Pattern Recognition: Identifying repetitive structures, sequences, or shapes within large datasets.

- Data-Driven Abstractions: Extracting simple, statistical patterns from massive quantities of information.

But its limitations are significant:

Shallow Understanding: AI struggles to form reusable and generalisable concepts when patterns are sparse, highly complex, or context-dependent. For example, while an AI model might recognise the concept of “a cat” in various images, it may fail to grasp the abstract notion of “feline” that applies across contexts, such as identifying a cat based on behaviour or skeletal structure. This limitation becomes evident in tasks requiring deeper comprehension, like understanding nuanced human intentions or reasoning about uncommon scenarios.

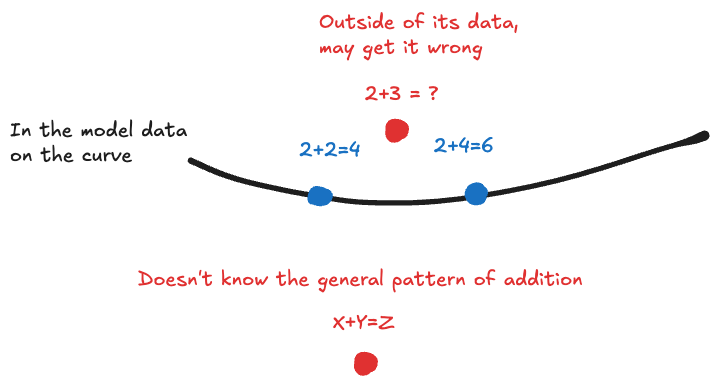

Challenges in Symbolic Reasoning: AI systems often falter at tasks requiring symbolic or rule-based reasoning, such as solving problems in the Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC) dataset, where humans excel by generalising abstract patterns. A simple example is basic arithmetic: while AI can often approximate sums accurately, it lacks the deeper symbolic understanding of addition. For instance, if trained on examples like “2 + 2 = 4,” an AI might misinterpret or fail entirely when confronted with novel symbolic contexts, like reasoning through algebraic equations such as “X + Y = Z” or “1,234,345 + 45,913 = 1280258“ or famously not being able to count the r’s in the word strawberry.

These limitations arise from fundamental aspects of how AI systems are designed:

Continuous Representations: AI represents data as continuous, numerical values in multidimensional spaces, which is excellent for recognising patterns and handling approximations, such as identifying faces in photos even when they’re blurry. However, this approach is inherently poor at discrete, rule-based reasoning—like applying precise symbolic logic—because it doesn’t “think” in terms of distinct categories or symbols.

Optimisation Bias in Training: AI models learn through a process called gradient descent, which optimises performance on training data by minimising errors. This method tends to prioritise pattern recognition and “shortcut learning” over true abstraction. For instance, an AI might learn that certain shapes in an image signal “dog,” but it doesn’t “understand” what a dog is in a transferable way, such as deducing “dog” from a verbal description or a completely abstract representation of the concept.

Dependence on Data: AI struggles when required to generalise from minimal examples or create abstractions from novel, sparse data. It has to be somewhere in its continuous representations to be able to interpolate the answer we would like.

Opportunities for Humans: Harnessing Our Unique Strengths

Humans have a unique advantage: the ability to identify and manipulate “atoms of meaning” through abstraction. While machines struggle to create truly reusable and generalisable patterns, humans excel at breaking down problems into their core elements and synthesising them into new, creative solutions.

This difference presents an opportunity. In the age of AI, humans can focus on developing deeper understanding and creativity, going beyond rote memorization to master fundamental principles. This involves searching for those atoms of meaning of the kaleidoscope hypothesis through:

First-Principles Thinking: Breaking problems down into their most basic truths and reasoning upward. The kaleidoscope hypothesis extends this idea by emphasising the recombination of these principles into larger, dynamic structures.

Game-Based Learning: Encouraging play and exploration to develop a deeper understanding of patterns and principles through play.

Expert-Curated Content backed by the best educational methods (see here and here): Designing learning experiences that push students beyond surface-level memorisation and into the realm of abstraction and synthesis.

The goal is through dealing with the first-principles and building on the principles through game-play and other content, we can synthesise or layer abstraction on top of abstraction as we build a library or tower of abstractions that help us to reason in more and more complex ways.

A Future of Collaboration: Humans and AI

As AI continues to advance, it will indeed continue to improve at interpolation and synthesis within defined bounds, performing rote and repetitive tasks with incredible efficiency. Humans, however, will remain indispensable for tasks requiring deep abstraction, symbolic reasoning, and the ability to extrapolate beyond the known.

The challenge for educators and learners is clear: How can we stay engaged and find meaning in a world increasingly driven by AI-generated content? The answer lies in mastering the patterns and abstractions that machines cannot. By deeply understanding the building blocks of our world, we can navigate complexity, create new paradigms, and ensure that humanity’s unique cognitive strengths remain at the forefront.

This essay is based off the recent Machine Learning Street Talk Podcast featuring François Chollet.